Celtic languages

| Celtic | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution: |

Formerly widespread in Europe; today British Isles, Brittany, Patagonia and Nova Scotia |

| Linguistic Classification: | Indo-European Celtic |

| Subdivisions: |

Continental Celtic

Insular Celtic

|

| ISO 639-2 and 639-5: | cel |

|

Indo-European topics |

|---|

| Indo-European languages (list) |

| Albanian · Armenian · Baltic Celtic · Germanic · Greek Indo-Iranian (Indo-Aryan, Iranian) Italic · Slavic extinct: Anatolian · Paleo-Balkan (Dacian, |

| Proto-Indo-European language |

| Vocabulary · Phonology · Sound laws · Ablaut · Root · Noun · Verb |

| Indo-European language-speaking peoples |

| Europe: Balts · Slavs · Albanians · Italics · Celts · Germanic peoples · Greeks · Paleo-Balkans (Illyrians · Thracians · Dacians) ·

Asia: Anatolians (Hittites, Luwians) · Armenians · Indo-Iranians (Iranians · Indo-Aryans) · Tocharians |

| Proto-Indo-Europeans |

| Homeland · Society · Religion |

| Indo-European studies |

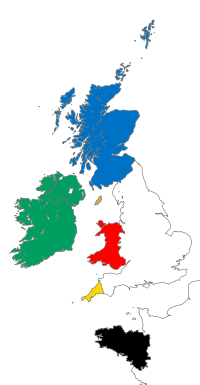

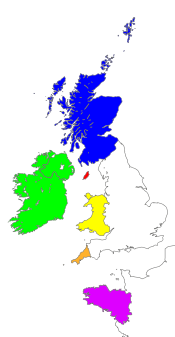

The Celtic languages (pronounced /ˈkɛltɪk/ or /ˈsɛltɪk/) are descended from Proto-Celtic, or "Common Celtic", a branch of the greater Indo-European language family. The term "Celtic" was used to describe this language group by Edward Lhuyd in 1707, having much earlier been used by Greek and Roman writers to describe tribes in central Gaul. During the 1st millennium BC, they were spoken across Europe, from the Bay of Biscay and the North Sea, up the Rhine and down the Danube to the Black Sea and the Upper Balkan Peninsula, and into Asia Minor (Galatia). Today, Celtic languages are limited to a few areas on the western fringe of Europe, notably Wales, Scotland, Ireland, the peninsula of Brittany in France, and Cornwall and the Isle of Man. Celtic languages are also spoken on Cape Breton Island and in Patagonia. The spread to Cape Breton and Patagonia occurred in modern times. Celtic languages were spoken in Australia before federation in 1901. Some people speak Celtic languages in the other Celtic diaspora areas of the United States [1], Canada, Australia [2] and New Zealand [3]. In all these areas the Celtic languages are now only spoken by minorities although there are continuing efforts at revival.

Contents |

Living dialects

SIL Ethnologue lists six "living" Celtic languages, of which four have retained a substantial number of native speakers. These are Welsh and Breton, descended from the British language of the Roman era, and Irish and Scottish Gaelic, descended from the common Hiberno-Scottish Gaelic of the Early Modern period.

The other two, Cornish and Manx, were extinct or near-extinct in the 20th century, and are now "living" only as the result of language revival efforts, with a small number of children brought up as bilingual speakers.

Taken together, there were roughly one million native speakers of Celtic languages as of the 2000s.

Demographics

| Language | native name | grouping | native speakers | total speakers | area | language body |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Welsh | Cymraeg | Brythonic | 750,000+: — Wales: 611,000[4] — England: 150,000[5] — Chubut Province, Argentina: 5,000[6] |

750,000+: — Wales: 611,000[4] — England: 150,000[5] — Chubut Province, Argentina: 5,000[6] |

Bwrdd yr Iaith Gymraeg | |

| Irish | Gaeilge | Goidelic | 62,157[7] | 1,738,384[8] [9] | Foras na Gaeilge | |

| Breton | Brezhoneg | Brythonic | 200,000 [10] | 200,000 [10] | Ofis ar Brezhoneg | |

| Scottish Gaelic | Gàidhlig | Goidelic | 92,400 | 92,400 [11] | Bòrd na Gàidhlig | |

| Cornish | Kernewek | Brythonic | 500 [12] | 2,000 [13] | Keskowethyans an Taves Kernewek | |

| Manx | Gaelg | Goidelic | 100 [14][15], including a small number of children who are new native speakers[16] | 1,700 [17] | Coonceil ny Gaelgey |

Mixed languages

- Shelta, a mix of the Irish, English and Romany languages (some 86,000 speakers in 2009).

- Bungi, a Métis mix of Scottish Gaelic, Cree and other languages (near-extinct).

- Some forms of Welsh-Romani also combined Romany itself with Welsh language and English language forms (extinct).

Classifications

Proto-Celtic divided into four sub-families:

- Gaulish and its close relatives Lepontic, Noric, and Galatian. These languages were once spoken in a wide arc from France to Turkey and from Belgium to northern Italy. They are now all extinct.

- Celtiberian, anciently spoken in the Iberian peninsula,[18] in parts of modern Aragón, Old Castile, and New Castile in Spain. Lusitanian, from Southern Portugal, may also have been a Celtic language. These are now also extinct.

- Goidelic, including Irish, Scottish Gaelic, and Manx. At one time there were Irish on the coast of southwest England and on the coast of north and south Wales.

- Brythonic, including Welsh, Breton, Cornish, Cumbric, and possibly also Pictish though this may be a sister language rather than a daughter of British (Common Brythonic).[19] Before the arrival of Scotti on the Isle of Man in the 9th century there may have been a Brythonic language in the Isle of Man[20]

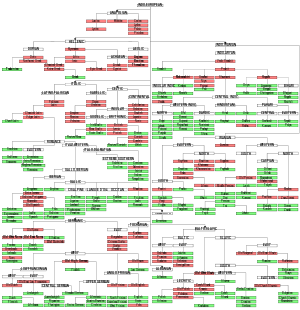

Scholarly handling of the Celtic languages has been rather argumentative owing to lack of much primary source data. Some scholars (such as Cowgill 1975; McCone 1991, 1992; and Schrijver 1995) distinguish Continental Celtic and Insular Celtic, arguing that the differences between the Goidelic and Brythonic languages arose after these split off from the Continental Celtic languages. Other scholars (such as Schmidt 1988) distinguish between P-Celtic and Q-Celtic, putting most of the Gaulish and Brythonic languages in the former group and the Goidelic and Celtiberian languages in the latter. The P-Celtic languages (also called Gallo-Brittonic) are sometimes seen (for example by Koch 1992) as a central innovating area as opposed to the more conservative peripheral Q-Celtic languages.

The Breton language is Brythonic, not Gaulish, though there may be some input from the latter.[21] When the Anglo-Saxons moved into Great Britain, several waves of the native Britons crossed the English Channel and landed in Brittany. They brought with them their Brythonic language, which evolved into Breton – still partially intelligible by modern Welsh and Cornish speakers.

In the P/Q classification scheme the first language to split off from Proto-Celtic was Gaelic. It has characteristics that some scholars see as archaic but others see as also being in the Brythonic languages (see Schmidt). With the Insular/Continental classification scheme the split of the former into Gaelic and Brythonic is seen as being late.

The distinction of Celtic into these four sub-families most likely occurred about 900 BC according to Gray and Atkinson[22][23] but, because of estimation uncertainty, it could be any time between 1200 and 800 BC. However, they only considered Gaelic and Brythonic. The controversial paper by Forster and Toth[24] included Gaulish and put the break-up much earlier at 3200 BC ± 1500 years. They support the Insular Celtic hypothesis. The early Celts were commonly associated with the archaeological Urnfield culture, the Hallstatt culture, and the La Tène culture, though the earlier assumption of association between language and culture is now considered to be less strong.

There are two main competing schemata of categorization. The older scheme, argued for by Schmidt (1988) among others, links Gaulish with Brythonic in a P-Celtic node, originally leaving just Goidelic as Q-Celtic. The difference between P and Q languages is the treatment of Proto-Celtic *kʷ, which became *p in the P-Celtic languages but *k in Goidelic. An example is the Proto-Celtic verb root *kʷrin- "to buy", which became pryn- in Welsh but cren- in Old Irish. However, a classification based on a single feature is seen as risky by its critics, particularly as the sound change occurs in other language groups (Oscan and Greek).

The other scheme, defended for example by McCone (1996), links Goidelic and Brythonic together as an Insular Celtic branch, while Gaulish and Celtiberian are referred to as Continental Celtic. According to this theory, the "P-Celtic" sound change of [kʷ] to [p] occurred independently or areally. The proponents of the Insular Celtic hypothesis point to other shared innovations among Insular Celtic languages, including inflected prepositions, VSO word order, and the lenition of intervocalic [m] to [β̃], a nasalized voiced bilabial fricative (an extremely rare sound). There is, however, no assumption that the Continental Celtic languages descend from a common "Proto-Continental Celtic" ancestor. Rather, the Insular/Continental schemata usually considers Celtiberian the first branch to split from Proto-Celtic, and the remaining group would later have split into Gaulish and Insular Celtic.

There are legitimate scholarly arguments in favour of both the Insular Celtic hypothesis and the P-Celtic/Q-Celtic hypothesis. Proponents of each schema dispute the accuracy and usefulness of the other's categories. However, since the 1970s the division into Insular and Continental Celtic has become the more widely held view (Cowgill 1975; McCone 1991, 1992; Schrijver 1995).

When referring only to the modern Celtic languages, since no Continental Celtic language has living descendants, "Q-Celtic" is equivalent to "Goidelic" and "P-Celtic" is equivalent to "Brythonic".

Within the Indo-European family, the Celtic languages have sometimes been placed with the Italic languages in a common Italo-Celtic subfamily, a hypothesis that is now largely discarded, in favour of the assumption of language contact between pre-Celtic and pre-Italic communities.

How the family tree of the Celtic languages is ordered depends on which hypothesis is used:

|

Insular/Continental hypothesis |

P-Celtic/Q-Celtic hypothesis |

Characteristics of Celtic languages

Although there are many differences between the individual Celtic languages, they do show many family resemblances. While none of these characteristics is necessarily unique to the Celtic languages, there are few if any other languages which possess them all. They include:

- consonant mutations (Insular Celtic only)

- inflected prepositions (Insular Celtic only)

- two grammatical genders (modern Insular Celtic only; Old Irish and the Continental languages had three genders)

- a vigesimal number system (counting by twenties)

- e.g. Cornish whetek ha dew ugens "fifty-six" (literally "sixteen and two twenty")

- verb-subject-object (VSO) word order (probably Insular Celtic only)

- an interplay between the subjunctive, future, imperfect, and habitual, to the point that some tenses and moods have ousted others

- an impersonal or autonomous verb form serving as a passive or intransitive

- Welsh dysgaf "I teach" vs. dysgir "is taught, one teaches", Irish "déanaim" "I do/make" vs. "déantar" "is done"

- no infinitives, replaced by a quasi-nominal verb form called the verbal noun or verbnoun

- frequent use of vowel mutation as a morphological device, e.g. formation of plurals, verbal stems, etc.

- use of preverbal particles to signal either subordination or illocutionary force of the following clause

- mutation-distinguished subordinators/relativizers

- particles for negation, interrogation, and occasionally for affirmative declarations

- infixed pronouns positioned between particles and verbs

- lack of simple verb for the imperfective "have" process, with possession conveyed by a composite structure, usually BE + preposition

- Cornish yma kath dhymm "I have a cat", literally "there is a cat to me"

- use of periphrastic phrases to express verbal tense, voice, or aspectual distinctions

- distinction by function of the two versions of BE verbs traditionally labelled substantive (or existential) and copula

- bifurcated demonstrative structure

- suffixed pronominal supplements, called confirming or supplementary pronouns

- use of singulars and/or special forms of counted nouns, and use of a singulative suffix to make singular forms from plurals, where older singulars have disappeared

Examples:

(Irish) Ná bac le mac an bhacaigh is ní bhacfaidh mac an bhacaigh leat.

(Literal translation) Don't bother with son the beggar's and not will-bother son the beggar's with-you.

- bhacaigh is the genitive of bacach. The igh the result of affection; the bh is the lenited form of b.

- leat is the second person singular inflected form of the preposition le.

- The order is verb subject object (VSO) in the second half - compare this to English or French which are normally Subject Verb Object in word order.

(Welsh) pedwar ar bymtheg a phedwar ugain

(literally) four on fifteen and four twenties

- bymtheg is a mutated form of pymtheg, which is pump ("five") plus deg ("ten"). Likewise, phedwar is a mutated form of pedwar.

- The multiples of ten are deg, ugain, deg ar hugain, deugain, hanner cant, trigain, deg a thrigain, pedwar ugain, deg a phedwar ugain, cant.

Comparison table

| Welsh | Cornish | Breton | Irish | Scottish Gaelic | Manx | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gwenynen | gwenenen | gwenanenn | beach, meach | seillean, beach | shellan | bee |

| cadair | cador | kador | cathaoir | cathair | caair | chair |

| caws | keus | keuz | cáis | càise | caashey | cheese |

| tu fas, tu allan | yn-mes | er-maez | amuigh/amach | a-muigh/a-mach | y-mooie/(y-)magh | outside |

| codwm | codha | kouezhañ | titim, tuitim | tuiteam | tuittym | (to) fall |

| gafr | gaver | gavr/gaor | gabhar | gobhar/gabhar | goayr | goat |

| tŷ | chy | ti | tigh, teach | taigh | tie | house |

| gwefus | gweus | gweuz | béal 'mouth' | bile | meill | lip |

| aber | aber | aber | inbhear | inbhir | inver | river mouth |

| rhif, nifer | nyver | niver | uimhir | àireamh | earroo | number |

| gellygen, peren | peren | perenn | piorra | peur/piar | peear | pear |

| ysgol | scol | skol | scoil | sgoil | scoill | school |

| ysmygu | megy | mogediñ | tabac a chaitheamh | smocainn | smookal | (to) smoke |

| seren | steren | ster(ed)enn | réalt | reult | reealt | star |

| heddiw | hedhyw | hiziv | inniu, inniubh | an-diugh, inniugh | jiu | today |

| chwibanu | whibana | c'hwibanat | feadaíl | feadghal | feddanagh | (to) whistle |

| chwarel | whel | arvez | cairéal | coireall/cuaraidh | quarral | quarry |

| llawn | leun | leun | lán | làn | laan | full |

| arian | arhans | arc'hant | airgead | airgead | argid | silver |

| arian, pres | mona | moneiz | airgead | airgead | argid | money |

Examples

Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights:

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

- Scottish Gaelic: Tha gach uile dhuine air a bhreth saor agus co-ionnan ann an urram 's ann an còirichean. Tha iad air am breth le reusan is le cogais agus mar sin bu chòir dhaibh a bhith beò nam measg fhein ann an spiorad bràthaireil.

- Irish: Saolaítear na daoine uile saor agus comhionann ina ndínit agus ina gcearta. Tá bua an réasúin agus an choinsiasa acu agus dlíd iad féin d'iompar de mheon bráithreachais i leith a chéile.

- Manx: Ta dagh ooilley pheiagh ruggit seyr as corrym ayns ard-cheim as kiartyn. Ren Jee feoiltaghey resoon as cooinsheanse orroo as by chair daue ymmyrkey ry cheilley myr braaraghyn.

- Welsh: Genir pawb yn rhydd ac yn gydradd â'i gilydd mewn urddas a hawliau. Fe'u cynysgaeddir â rheswm a chydwybod, a dylai pawb ymddwyn y naill at y llall mewn ysbryd cymodlon.

- Cornish: Pub den oll yw genys frank ha kehaval yn dynita ha gwiryow. Yth yns i enduys gans reson ha cowses hag y tal dhedhans gwul dhe udn orth y gila yn spyrys a vredereth.

- Breton: Dieub ha par en o dellezegezh hag o gwirioù eo ganet an holl dud. Poell ha skiant zo dezho ha dleout a reont bevañ an eil gant egile en ur spered a genvreudeuriezh.

Notes

- ↑ "Language by State - Scottish Gaelic" on Modern Language Association website. Retrieved 27 December 2007

- ↑ "Languages Spoken At Home" from Australian Government Office of Multicultural Interests website. Retrieved 27 December 2007

- ↑ Languages Spoken:Total Responses from Statistics New Zealand website. Retrieved 5 August 2008

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "2004 Welsh Language Use Survey: the report - Welsh Language Board". http://www.byig-wlb.org.uk/english/publications/publications/332.doc. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "Refworld | World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples - United Kingdom : Welsh". UNHCR. http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/topic,463af2212,488f25df2,49749c8cc,0.html. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "h2g2 - Y Wladfa - The Welsh in Patagonia". BBC. http://www.bbc.co.uk/dna/h2g2/A1163503. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ language

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 The French census of 2001 recorded about 270,000 speakers, with a yearly decline of about 10,000 speakers. The site oui au breton estimates a number of about 200,000 speakers as of 2008.

- ↑ BBC News: Mixed report on Gaelic language

- ↑ some 500 children brought up as bilingual native speakers (2003 estimate, SIL Ethnologue).

- ↑ s About 2,000 fluent speakers. "'South West:TeachingEnglish:British Council:BBC". BBC/British Council website (BBC). 2010. http://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/uk-languages/south-west. Retrieved 2010-02-09.

- ↑ Anyone here speak Jersey?

- ↑ Fockle ny ghaa: schoolchildren take charge

- ↑ Documentation for ISO 639 identifier: glv

- ↑ 2006 Official Census, Isle of Man

- ↑ Ethnographic Map of Pre-Roman Iberia (circa 200 B.C.)

- ↑ Kenneth H. Jackson suggested that there were two Pictish languages, a pre-Indo-European one and a Pretenic Celtic one. This has been challenged by some scholars. See Katherine Forsyth's "Language in Pictland: the case against 'non-Indo-European Pictish'" EtextPDF (27.8 MB). See also the introduction by James & Taylor to the "Index of Celtic and Other Elements in W.J.Watson's 'The History of the Celtic Place-names of Scotland'" EtextPDF (172 KB). Compare also the treatment of Pictish in Price's The Languages of Britain (1984) with his Languages in Britain & Ireland (2000).

- ↑ Kenneth Jackson used the term "Brittonic" for the form of the British language after the changes in the 6th century.

- ↑ Barbour and Carmichael, Stephen and Cathie (2000). Language and nationalism in Europe. Oxford University Press. pp. 56. ISBN 9780198236719. http://books.google.com/?id=1ixmu8Iga7gC&pg=PA56&lpg=PA56&dq=Breton+Gaulish+words&q=Breton%20Gaulish%20words.

- ↑ Gray and Atkinson, RD; Atkinson, QD (2003). "Language-tree divergence times support the Anatolian theory of Indo-European origin". Nature 426 (6965): 435–439. doi:10.1038/nature02029. PMID 14647380.

- ↑ Rexova, K.; Frynta, D and Zrzavy, J. (2003). "Cladistic analysis of languages: Indo-European classification based on lexicostatistical data". Cladistics 19: 120–127. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.2003.tb00299.x.

- ↑ Forster, Peter; Toth, Alfred (2003). Toward a phylogenetic chronology of ancient Gaulish, Celtic, and Indo-European. The National Academy of Sciences.

See also

- A Swadesh list of the modern Celtic languages

- Language families and languages

- Celtic League (political organisation)

- Celtic Congress

References

- Ball, Martin J. & James Fife (ed.) (1993). The Celtic Languages. London: Routledge. ISBN 0415010357.

- Borsley, Robert D. & Ian Roberts (ed.) (1996). The Syntax of the Celtic Languages: A Comparative Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521481600.

- Cowgill, Warren (1975). "The origins of the Insular Celtic conjunct and absolute verbal endings". In H. Rix (ed.). Flexion und Wortbildung: Akten der V. Fachtagung der Indogermanischen Gesellschaft, Regensburg, 9.–14. September 1973. Wiesbaden: Reichert. pp. 40–70. ISBN 3-920153-40-5.

- Celtic Linguistics, 1700-1850 (2000). London; New York: Routledge. 8 vol.s comprising 15 texts originally published between 1706 and 1844.

- Forster, Peter and Toth, Alfred. Towards a phylogenetic chronology of ancient Gaulish, Celtic and Indo-European PNAS Vol 100/13, July 22, 2003.

- Gray, Russell and Atkinson, Quintin. Language-tree divergence times support the Anatolian theory of Indo-European origin Nature Vol 426, 27 Nov 2003.

- Hindley, Reg (1990). The Death of the Irish Language: A Qualified Obituary. London; New York: Routledge. ISBN 0415043395.

- Lewis, Henry & Holger Pedersen (1989). A Concise Comparative Celtic Grammar. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 3525261020.

- McCone, Kim (1991). "The PIE stops and syllabic nasals in Celtic". Studia Celtica Japonica 4: 37–69.

- McCone, Kim (1992). "Relative Chronologie: Keltisch". In R. Beekes, A. Lubotsky, and J. Weitenberg (eds.). Rekonstruktion und relative Chronologie: Akten Der VIII. Fachtagung Der Indogermanischen Gesellschaft, Leiden, 31. August–4. September 1987. Institut für Sprachwissenschaft der Universität Innsbruck. pp. 12–39. ISBN 3-85124-613-6.

- McCone, K. (1996). Towards a Relative Chronology of Ancient and Medieval Celtic Sound Change. Maynooth: Department of Old and Middle Irish, St. Patrick's College. ISBN 0-901519-40-5.

- Russell, Paul (1995). An Introduction to the Celtic Languages. London; New York: Longman. ISBN 0582100828.

- Schmidt, K. H. (1988). "On the reconstruction of Proto-Celtic". In G. W. MacLennan. Proceedings of the First North American Congress of Celtic Studies, Ottawa 1986. Ottawa: Chair of Celtic Studies. pp. 231–48. ISBN 0-09-693260-0.

- Schrijver, Peter (1995). Studies in British Celtic historical phonology. Amsterdam: Rodopi. ISBN 90-5183-820-4.

External links

- Aberdeen University Celtic Department

- Ethnologue report for Celtic languages

- "Labara: An Introduction to the Celtic Languages", by Meredith Richard

- Celts and Celtic Languages

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||